FMP - Production Skills

Friday, 19 December 2014

Thursday, 18 December 2014

Production Report

The first post-production workshops covered the basics of

editing with AVID: creating a project in the correct settings, managing bins

and starting a sequence on the timeline. We were then introduced to the

source/record layout and writing footage to audio and video tracks. With this basic knowledge we were given the brief for the first skills task, to create a five minute

documentary about spoken word poetry using footage from the longer film.

The first challenge was the amount of time it took to import

and label the footage and sound. This ultimately meant that we had no rough cut

to receive constructive feedback on by the next session. This was further

complicated by our inexperience working with the software and not having access

to half of the footage or sound files from the interviews.

On reflection, we spent too much time at this stage

labelling the footage and sorting the files, but on the second task we managed

our time more effectively. However, the interview transcripts I made (Fig.1)

did prove very helpful whilst navigating the footage for sound-bytes, and in building

a logical structure for the film later on.

|

| Fig. 1 |

We used the feedback that another classmate received to

inform our rough cut as we started editing. We were advised to engage the

audience straight away by opening with the film’s subject Addie reciting a

poem. Other advice which we noted and tried to implement included the ‘rule of

three’ to establish a new setting, creating our own subtext within the footage and

most importantly reinforcing any assertions with ‘evidence’.

Working on the documentary task independently we learnt a

number of essential AVID techniques not covered in the workshops: splitting

footage, key-framing audio and managing multiple tracks (Fig.2). This came

mainly through looking online for tutorials on how to achieve the effect we

wanted. We also gained a better understanding of the various editing modes in

the ‘smart tool’; their different uses, effects and how to quickly switch between

them without error.

|

| Fig. 2 |

Further workshops mainly covered media management due to

issues with systems crashing and losing files. We were shown how to access the

media, project and bin files stored in AVID’s database, and then how to use the

media tool to transfer our project across the shared network. We also learned

how to export in the correct format (Fig.3), using the Avid 1:1 codec and

minimal compression. In MPEG streamclip we then converted the file into an MP4

optimised for Vimeo upload.

|

| Fig. 3 |

After presenting our documentary fine cut we received

specific criticism and more general feedback for future projects. The more

general feedback included not having ‘gold-fishing’ (mouths moving without

sound), not repeating ideas and finding creative ways to disguise the

production.

For our edit we were praised for its cohesive structure, pacing

and choice of strong interview sound-bytes. Our ending was identified as an

area for improvement, fading to black twice (Fig.4). We were advised to try and

consolidate them in the future, as short film audiences prefer a definite

ending. Another criticism was that the move to Addie talking about nature and

the mechanics of poetry was unneeded. However I feel it was a key part of the

story, and was necessary to keep the focus on Addie’ and for a change of pace

and environment.

|

| Fig. 4 |

Our second task was to create a five minute drama piece

using footage from ‘Flatline’, a short film about two paramedics with conflicting

approaches to dealing with their patients. We watched the final version of the

film on Vimeo to get an idea of the film’s structure and then began our rough

assembly. The main challenge we faced on this task was not having access to

many of the shots used in the final film. Footage from the opening montage, a

scene in a hospital corridor and almost the entire last scene were missing, as

well as the separate audio recordings. With only camera sound available, this

meant we had to cross-fade most of the audio clips together and loop parts of

the track to fill in any gaps.

One of the more problematic sequences in the film was the

conversation between the protagonist Alex and a doctor in the hospital

corridor. We had options of editing between a master shot and close-ups of both

characters, but the performances were inconsistent, the lighting poor and

framing sometimes awkward. After trying various different ways around this, we

decided to keep the scene in a wide for the most part, cutting into close-up

only at the end (Fig.5). On reflection, this was not the best choice as it

meant we had no control over pacing and line delivery.

|

| Fig. 5 |

For some of the scenes we had a lot of different angles to

experiment with, so the learning at this stage was avoiding over-cutting,

thinking about the effects of each edit and ensuring they were motivated by

what we were trying to achieve in the scene. An example of this is in a scene

where the two main characters are sat in the ambulance talking. We used a two-shot

to show Alex’s growing agitation and then, after he lashes out at Mike, used

single shots to convey the conflict between them visually (Fig.6). To improve

the pace in other sequences we cut into the scene as late as possible, removing

entrances, exits or unnecessary pauses that didn’t contribute to the story.

|

| Fig. 6 |

For this task we also used various sound effects we sourced

online. We went through the film and noted down spot FX such as the alarm clock

and ambiences like the supermarket and hospital corridor. For the Edgar

Wright-inspired transition sequences I also added new elements of sound design,

such as fast ticking and cartoonish whoosh sounds for added pace. After

introducing these sounds, we key-framed audio volume and used EQ to balance

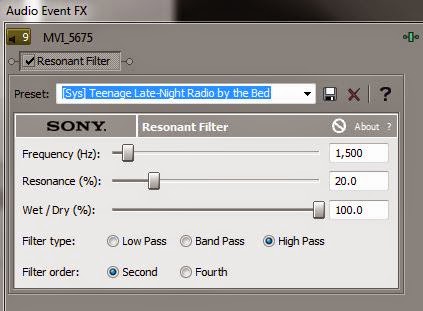

them in the mix. To make the voice sound as though coming over the radio, I

used the ‘Resonant Filter’ in Sony Vegas which has a preset for such an effect

(Fig.7). In a later workshop we were introduced to the Audio Suite in AVID and shown

how to apply audio effects to individual clips, which would have worked here as

well.

|

| Fig. 7 |

After presenting our fine cut we received criticism and

feedback for future drama projects. The hospital corridor scene was highlighted

as our only area for improvement due to the performance in the clip we had

chosen to use. Other general advice included cutting on movement to disguise

the cut, always showing what a character is looking at and avoiding over-cutting

scenes with multiple available angles.

I took this advice

into the final task we were given, editing a single scene from a short comedy. The

first challenge of this was working out the structure of the scene without a

reference (as we had with the other tasks) and finding footage to extract from the

one video file we were given.

After viewing all of the footage the structure became clear

and I began a rough assembly. As a single scene this was simpler and quicker

than the other tasks, but with the comedy coming from the pace and timing of

the editing, I was more considered in my choice and length of shot. For example, when the two characters first

walk into the house I stayed on the reaction of the woman, which conveyed her initial

impressions of Winston. In addition, I inserted a shot of Winston speaking directly

to camera to give the viewer the same jarring effect, and used ‘pan and zoom’

to crop the frame and focus on her reaction (Fig.9).

|

| Fig. 9 |

One of the main issues was maintaining continuity, as the

positions and movements of the actors often differed between takes. In some

cases I was able to use other footage, stay on the shot or overlap sound to

work around this. However, for others I sacrificed the continuity either for a

take with stronger performances or to improve pacing, as this was essential to create

comedy in the scene. For the most part, the comedy came from the reactions of

the posh couple to the two main characters, so I made full use of the shots of

them.

Following the rough assembly, I condensed parts of the scene

that I felt were too slow. For example, instead of showing the woman placing

the food on the table, I moved the line ‘I hope you’re hungry Winston’ to when

she enters with the trolley, cutting straight to the man ready to cut the beef.

To ease this transition I added a layer of light dinner party music, also

conveying the status of the hosts and creating awkward tension as they eat in

silence. I cut the music later when

Winston abruptly leaves, exaggerating the disruption he causes (Fig.10).

|

| Fig. 10 |

Finally, I applied some light colour correction to each shot in the film, using what we were shown in workshops. I first used colour curves to adjust the contrast and removed the yellow tinge from the film with the colour wheels (Fig.11). However, this made the film look too cold and didn't fit the tone, so instead I increased saturation to bring out the colour on the table, and used curves to bring up the brightness (Fig.12). I tried to keep the effect subtle and consistent throughout, but being new to colour correction there are some times where it is consistent.

|

| Fig. 11 |

|

| After |

|

| Before |

Monday, 15 December 2014

'Shutter Island' Analysis

After its unconventional editing style was mentioned in an interview with Thelma Schoonmaker and a video essay by Tony Zhou, I watched and analysed 'Shutter Island' (Martin Scorsese, 2010). In the film, U.S. Marshal Teddy Daniels and his partner are investigating the disappearance of a patient at a mental hospital/correctional facility on 'Shutter Island'. The editing plays a large part in conveying Teddy's own damaged mental state following the death of his wife, and also in creating a sense of tension and danger from the moment they set foot on the island.

The film makes heavy use of flashbacks as a means of exposition but also in visualizing Teddy's damaged mental state. In the opening scene, a question about Teddy's wife triggers a flashback sequence. The editing is fast and fragmented, conveying an intrusive thought as he remembers his wife. The sound of the scene fades out to leave a sustained low tone and ghostly choir, contrasting with and disrupting the happiness shown in the images.

As we return to the boat, there is a jarring freeze-frame of Teddy's wife, quick enough for the audience to wonder whether they actually saw it.

This device is important as one of the key themes the film develops is whether our own memories can be trusted. This first flashback sequence therefore establishes a number of things:

To a similar effect as the freeze-frame in the first sequence, deliberate continuity errors, jump-cuts and later, reversed shots (when he is smoking) convey Teddy's fragmented memory and the break down of reality. As these effects are jarring for the viewer, we share Teddy's sense that these flashbacks are difficult and painful to relive. Upon exiting this sequence, as with the other flashbacks, the soft music cuts out abruptly to foreground his sudden return to reality.

As well as conveying the break from reality in the flashbacks, the breakdown of the editing is even more important when seen in the context of the whole story. At the end of the film we are told that Teddy's memories of his wife are all false, and that he has created them as part of an alternate self. With this knowledge, we can view the jump-cuts, freeze-frames and other jarring devices as hints that the details in Teddy's memories do not sit right (or do not create a full, coherent story). The other sequences outside this all flow naturally. It is as though they have been placed together and constructed artificially in Teddy's mind using elements from true events, perhaps even mirroring the editing process.

At the end of the film, Teddy has a flashback where he relives the actual events which led to the death of his wife and children. As this is reality, none of the devices which highlight the surrealism of the other sequences are used. The scene plays out in real time with no jumps, and the colours, lighting and sounds are all natural.

Notable also is the absence of the bright white flash which precedes the other flashbacks, again foregrounding this is 'reality'.

Another device used in the flashbacks and throughout the film is POV shots. As a viewer joining Teddy at the start of the film, we believe both him and the stories about his past. When, at the end of the film, this is all revealed to be false, we share his sense of confusion and undergo a similar process of reflection and erasure. The POV shots in the film build to this as we have experienced events exactly as Teddy has experienced them (being inside his head), including even his intrusive flashbacks. As a result we doubt our own memories of what we've seen in the film, just as Teddy does of what he's experienced.

Key moments in the film make use of POV shots to connect the viewer with Teddy's emotions. For example, the build of tension as we enter the facility's armoured gates, the sense of unease as he enters the hospital, the close analysis of the subjects he is interviewing among many others.

Other effective shots include fast close-ups of the door and repeated framing of the characters behind bars - both emphasizing that they are trapped and foreshadowing the revelation that Teddy is already a patient at the facility.

Notable also is the repeated framing of the staff and guards in the centre of the frame between Teddy and Chuck. By blocking the screen we get a sense they are a barrier or obstruction to their investigation, immediately raising suspicions around their character. The difference in framing size between them and Teddy is intimidating, asserting that they are the figures of authority.

The angle of the shot, looking at their backs (repeated in the shot below), is also slightly unnerving for the audience, suggesting that they are hiding something from them, adding to the sense of unease and suspicion.

The film makes heavy use of flashbacks as a means of exposition but also in visualizing Teddy's damaged mental state. In the opening scene, a question about Teddy's wife triggers a flashback sequence. The editing is fast and fragmented, conveying an intrusive thought as he remembers his wife. The sound of the scene fades out to leave a sustained low tone and ghostly choir, contrasting with and disrupting the happiness shown in the images.

This device is important as one of the key themes the film develops is whether our own memories can be trusted. This first flashback sequence therefore establishes a number of things:

- Provides exposition about Teddy's past with his wife

- Fast pace and contrasting music - establishes that the memory is intrusive and sets a darker tone

- Freeze-frame - Conveys Teddy's fragmented memory and damaged mental state

- Engages the viewer and introduces the key theme of not trusting our perceptions or memories

To a similar effect as the freeze-frame in the first sequence, deliberate continuity errors, jump-cuts and later, reversed shots (when he is smoking) convey Teddy's fragmented memory and the break down of reality. As these effects are jarring for the viewer, we share Teddy's sense that these flashbacks are difficult and painful to relive. Upon exiting this sequence, as with the other flashbacks, the soft music cuts out abruptly to foreground his sudden return to reality.

As well as conveying the break from reality in the flashbacks, the breakdown of the editing is even more important when seen in the context of the whole story. At the end of the film we are told that Teddy's memories of his wife are all false, and that he has created them as part of an alternate self. With this knowledge, we can view the jump-cuts, freeze-frames and other jarring devices as hints that the details in Teddy's memories do not sit right (or do not create a full, coherent story). The other sequences outside this all flow naturally. It is as though they have been placed together and constructed artificially in Teddy's mind using elements from true events, perhaps even mirroring the editing process.

At the end of the film, Teddy has a flashback where he relives the actual events which led to the death of his wife and children. As this is reality, none of the devices which highlight the surrealism of the other sequences are used. The scene plays out in real time with no jumps, and the colours, lighting and sounds are all natural.

Notable also is the absence of the bright white flash which precedes the other flashbacks, again foregrounding this is 'reality'.

Another device used in the flashbacks and throughout the film is POV shots. As a viewer joining Teddy at the start of the film, we believe both him and the stories about his past. When, at the end of the film, this is all revealed to be false, we share his sense of confusion and undergo a similar process of reflection and erasure. The POV shots in the film build to this as we have experienced events exactly as Teddy has experienced them (being inside his head), including even his intrusive flashbacks. As a result we doubt our own memories of what we've seen in the film, just as Teddy does of what he's experienced.

Key moments in the film make use of POV shots to connect the viewer with Teddy's emotions. For example, the build of tension as we enter the facility's armoured gates, the sense of unease as he enters the hospital, the close analysis of the subjects he is interviewing among many others.

Notable also is the repeated framing of the staff and guards in the centre of the frame between Teddy and Chuck. By blocking the screen we get a sense they are a barrier or obstruction to their investigation, immediately raising suspicions around their character. The difference in framing size between them and Teddy is intimidating, asserting that they are the figures of authority.

The angle of the shot, looking at their backs (repeated in the shot below), is also slightly unnerving for the audience, suggesting that they are hiding something from them, adding to the sense of unease and suspicion.

Friday, 12 December 2014

Video Essays: 'Every Frame a Painting'

In this popular YouTube series Tony Zhou analyses the craft of a number of directors and films. In his educational video essays he covers a variety of topics, such as Spielberg's use of long takes, David Fincher's repeated techniques and Scorsese's use of silence. As a freelance editor himself, Zhou's videos often have a particular focus on how some scenes are edited to create meaning, giving insight to the level of thought contained in every choice of shot. Below I have summarized the main points from his best videos:

In this video Zhou analyses the first meeting between the two main characters in 'The Silence of the Lambs' (Jonathan Demme, 1991). He identifies both characters as 'wanting something' from the other, and goes into a shot-by-shot analysis to determine who 'wins' the shifting power struggle in the scene.

Here Tony explores director David Fincher's signature techniques, and interestingly the devices he chooses not to use in his films.

Scorsese is well-known for his use of music in his films, but in this video Zhou highlights his most powerful uses of silence.

In this video Zhou analyses the first meeting between the two main characters in 'The Silence of the Lambs' (Jonathan Demme, 1991). He identifies both characters as 'wanting something' from the other, and goes into a shot-by-shot analysis to determine who 'wins' the shifting power struggle in the scene.

- Both characters looking directly into the lens - examining each other for the first time.

- Similar framing shows both characters as equals, even though Lecter is in jail.

- As he gains the power, shift to shot looking down on her and up at him.

- She looks slightly off-camera but he looks into the lens - we're 'inside her head'. Reinforced by camera movements looking around the room as she does.

- Change to a 'standoffish angle' of Lecter whenever she's obvious about her intents.

- Shift to Lecter's POV to show his genuine curiosity.

- CU of survey establishes its importance.

- As Lecter gains power, dolly moves to frame him normally. Clarice framed off-center, she's been knocked 'off-balance'.

- Scene ends with first two-shot containing both characters - establishes the beginning of their relationship in the film.

Here Tony explores director David Fincher's signature techniques, and interestingly the devices he chooses not to use in his films.

- Handheld - uses it very rarely, usually once or twice per film.

- Final scene of 'Seven' (David Fincher, 1995) - shaky camera for the two cops, tripod for John Doe. Conveys who is and isn't in control during the scene.

- Human-operated camera - no shaky camera or 'mistakes' in shots. Camera is 'omniscient', and has no personality to it.

- Close-ups - uses them sparingly, because it tells the audience 'look at this, its important'.

- No unmotivated camera moves - tries to frame in simple proscenium, 'this is what is happening'.

Zhou then breaks down a simple scene in 'Seven' of three characters talking, showing how despite these limitations he manages to create relationships clearly and effectively.

- Shot/Reverse shot sequence between Somerset and the Chief

- Difference in frame size between Somerset and Chief shows topic is more important to Somerset.

- Change to a different, profile angle of the two characters to show how Mills is trying to get into the conversation.

- Eye-line not matching between Mills and Somerset, shows that he's being ignored.

- CU of Chief used when he dismisses Mills, emphatic and important.

Fincher has become more subtle throughout his career also, making use of space in the frame - 'cutting to an empty chair, or a space for an absent husband'.

Scorsese is well-known for his use of music in his films, but in this video Zhou highlights his most powerful uses of silence.

- 'Raging Bull' (Martin Scorsese, 1980) - Pulled all the SFX out the track at the end of the fight, creating a numbing effect that links the audience with the main character.

- 'Goodfellas' (Martin Scorsese, 1990) - "How the fuck am I funny?" scene. Silence used to create a central dramatic beat before a release of tension.

- In Scorsese's filmography, silence is used to precede an important character choice - 'such as choosing not to fight or choosing whether to take the money'

- The sound design is used to create an emotional structure for the film - each fight in 'Raging Bull' is preceded by a quiet domestic moment, allowing harsh cuts into the fight.

He also discusses the state of silence in modern films, the use of which is becoming more rare. A comparison is drawn between death scenes in the original 'Superman' (Richard Donner, 1978) and last year's reboot 'Man of Steel' (Zack Snyder, 2013). Whereas in the original Superman we are allowed to watch the build up and explosive release of emotion in its entirety without sound, the reboot continues music throughout the scene - detracting from its potential impact.

In a similar vein to his video on Edgar Wright's use of visual comedy, this video essay looks at how Jackie Chan creates action and comedy in his films. In an interview clip Chan describes the most important part as being the editing - 'most of the directors don't know how to edit.'

As Zhou describes, modern action films have adopted the 'Bourne' visual style of shaky cameras, motion blur and audience confusion to add intensity to fight sequences. In contrast, the success of such sequences in the work of Jackie Chan has come from being able to see everything that happens, and sticking to the rhythm of the scene. Whereas most action films cut on the impact of a hit to increase its impact, Chan gives the audience time to watch it happen, arguably to a greater effect.

Also covered in the video is the choice of shots used. Zhou explains the idea of including both action and reaction in the same shot, and how cutting between them individually works less successfully. Comparing similar scenes in 'Rush Hour 3' (Brett Ratner, 2007) and 'Police Story 2' (Jackie Chan, 1988), we can see that increasing the number of cuts actually detracts from the action and danger in the scene, much to the opposite of the intended effect.

Thursday, 11 December 2014

Video: Editing Interview Footage - Tips and Techniques

In this video, condensed from a 3-hour editing session, an editor is given interview and B-roll footage to create a short video without any other information. The video being made is a promotional video for a swimming instructor containing an interview and cutaway shots. Although he is working with Final Cut Pro, he gives a number of useful tips to speed up the editing workflow and to quickly identify and start constructing a story. Below I've summarized the main points made in the video:

- Choosing between a 'cold' or a 'warm' opening - going straight into the story (cold) or starting with their name and other personal information (warm).

- When looking at interview footage for the first time, place markers on the clip for good soundbites and best parts. Label these markers at the side to summarize the topic at that particular point.

- Most important part is working out the story they want to tell. They decide quickly what details they want to include and what they want to omit to find the story in the footage.

- Working out the different 'ideas' in the story and how they can be structured to fit together - how the story should develop. For example, one idea is the story of how the woman got into swimming, and another what the school aims to do.

- Finding a part that sounds like a beginning to the story e.g. 'I started swimming when I was six...'

- Editing workflow - moving between different saved versions and from rough assembly to fine cut

- Using music to ease emotional change and transition between different ideas

However, some of the decisions he makes in the film feel forced or too literal. For example, he uses a dissolve into the cutaway footage when the subject begins to talk about her dreams. Also, a slow push-in when she's talking about a serious topic is perhaps too overt. Additionally, as a personal choice I would look at the B-roll footage before locking in the interview cut, to see where links can be made and any assertions in the interview backed with evidence.

Monday, 8 December 2014

Video Essay: Contrapuntal Music

This video essay explores the concept of counterpoint in

film music. Conventional film music, which underscores and parallels the

emotion of the image, is ‘homophonous’. Counterpoint is created when the music

deliberately contradicts the ‘character of the images’.

'Music not only accompanies the images but it interferes deeply in the complex connection between the film, the filmmaker and the audience'

For example, in ‘Jarhead’

(Sam Mendes, 2005), the song ‘Don’t Worry, Be Happy’ is used over a highly

stressful fight scene, creating counterpoint.

Another example of contrapuntal music is the use of the song 'Lovely Day' over a scene of Aron struggling whilst trapped in '127 Hours' (Danny Boyle, 2010)

In such cases, the music used is independent from the image:

differing in rhythm, emotional expression or lyrics. Through this separation, it

is claimed that the music becomes as equally important as the visuals. This

dynamic of the visual ‘thesis’ and auditory ‘antithesis’ creates a new meaning

in the film which is to be ‘decoded’ by the audience – adding intellectual and

artistic value to the film.The most interesting point raised is that the use of

contrapuntal music has a variety of effects on the film/scene’s message.

- Moralization – in Michael Moore’s ‘Bowling For Columbine’ (2002), the use of ‘What a Wonderful World’ over images of war forces us to confront or question our morality.

- Philosophical – in ‘Chungking Express’ (Wong Kar, Wai, 1994), the use of the song ‘California Dream’ conveys the character’s philosophy and wishes to escape his environment.

- Dramatization – a contrast between soft music and images of destruction in ‘Miasto Nieujarzmione’ (1950, Jerzy Zarzycki) enhances the drama.

- Decharacterization - classical music played over a fight scene in 'A Clockwork Orange' (Stanley Kubrick, 1971) adds a darkly comic tone, as though it is a dance.

This change of meaning is suggested to be the musical equivalent of the 'Kuleshov effect'. With contrapuntal music, the music and the images are two independent elements, and neither is dominating or supporting the other. As a result, the viewers derive meaning from both elements, enhancing their engagement with the film.

Scene Analysis: 'City of God' (2002)

Following a list of the '10 Most Effective Editing Moments' I watched recently, I watched the opening sequence of Fernando Meirelles's 'City of God' (2002) and analysed its production and editing style.

- Very quick cuts of knife being sharpened - creates immediate sense of danger.

- Fast-paced samba music creates excitement and hints at location before any other context provided.

- Fast cuts and elliptical editing between close-ups: vegetables, chickens, feet dancing, musical instruments - party atmosphere, immediate intensity. Also establishes claustrophobia of the favelas.

- Handheld shots add authentic, documentary style. Links to the film's portrayal of real issues.

- Chasing the chicken through the streets. Overhead shots and tracking shots show density of location - links with the main characters' inability to escape and sets them up as targets.

- Music stops as new characters introduced, resumes as we cut back to the chicken.

- Cutting back and forth between other chicken and the other characters creates a sense of the two groups crossing paths, and some similar angles create sense that they are being chased.

- Music stops, changes to a darker, serious tone as the two groups see each other for first time. Slow-motion stresses importance of the moment, hints at back-story and establishes him as dangerous.

- Line of men pointing guns towards the camera - we are immediately allied with the young boys.

- 180 degree spin between police and men, conveys how main character will be caught between the two groups in the film. Both groups aiming guns in his direction, links to the police being corrupt.

- 360 degree camera spin transition. Clock SFX rewinding, going back in time. Title card 'The Sixties' gives context about scene, contrast in colour schemes (dark, shadowy blue vs bright, golden yellow) creates sense of nostalgia - repeated motif in film.

- Leading lines of the wide shot point towards boy, reinforces him as the central character.

- Buildings transition into open field, relieve us of claustrophobic, tense atmosphere.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)